Issue 8: The Gun Alley Murder

This case refers to the rape and murder of 12-year-old Alma Tirtschke that happened in Melbourne in 1921. Most recently has become known as a miscarriage of justice.

For just a 12-year-old Alma had already had a hard family life. Nell Alma Tritshke, known simply as Alma was born on 14 May 1909 in a mining settlement in Western Australia. She was the first of two daughters born to Charles Tirtshke and Nell Alger. By 1911 the family was in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) for Charles’ work, there his second daughter, Viola, was born in 1912. It was unfortunately upon their return journey to Australia in 1914 that Nell died of complications relating to the third pregnancy. She was subsequently buried at sea. Charles could not manage being the sole career for his daughters in Melbourne. He returned to Western Australia to work on the goldfields. Alma and Viola were cared for by their grandparents, Henry and Elizabeth Tirschke, who were assisted by their five adult daughters. By the time of the murder it was just the two girls and their grandmother, Henry having already died.

The circumstances that surround Alma Tirtschke’s death started out as a normal day. It was common to do errands for the family. That morning her aunt had asked if she would go to the butchers Bennet and Woolcock Pty. Ltd. Located on Swanston Street where she would get a parcel of meat. The aunt’s husband worked at the butchers. From there she was to deliver it to her aunt’s house located in Collins Street. Then return home. The round trip should not take more than 2 hours. She left her grandma’s at around noon.

It wasn’t until the next morning that a man called Errington found himself on the streets of Melbourne near the Eastern Market. This was a block located between Little Collins and Bourke Street (where the Commonwealth Bank and Vic Roads are today). It was here that he found empty bottles that had been left by bar patrons the night before. At the time it was common knowledge that a decent income could be made from collecting them and turning them in for recycling. The area where Errington found good pickings were a hub of night-time carousing; a warren of laneways and cul-de-sacs, small bars, betting shops and brothels.

It was as Errington took himself into Gun Alley, a dead-end, L-shaped lane. It ran off the south of Little Collins street and he was unaware of the horror he was about to stumble upon. In the dawn of the morning, the streets were quiet - Errington was stunned to find the body of a dead, naked girl. He could tell she was only a child. She lay there on her back with her legs bent under her. Errington ran to get help and upon police coming to the body it was soon identified as Alma Tritschke. She was reported missing the day before.

The Crime

The investigation of Alma Tirtschke's murder was charged to two men, John Brophy and Fred Piggott, both senior detectives in the Criminal Investigation Bureau.

Piggott had risen through the ranks to become a well known public figure. He had previously been involved with several high-profile cases; however, this would turn out to be one of his toughest. Right off the bat, the detectives did not have a lot to go on. First off, they were at least 10 or more hours behind the perpetrator. There were no witnesses to the actual murder and there was little in the way of physical evidence.

It was determined that she had been sexually assaulted. Her cause of death was determined to be strangulation and that the murder site was somewhere other than Gun Alley, as her body had been dumped there.

Alma’s clothes were never found. It was established that whoever the perpetrator most likely had some privacy. This was deduced by that Alma’s body had appeared to be washed, as a measure of removing trace evidence. The search of the surrounding area lasting 2 days yielded no further clues.

The location of the crime added to the complications of the crime. Where Alma was found in Gun Alley, especially near the Eastern Market was known as a disreputable part of town. As is usually the case with residents that resided in that area, they were reluctant to assist police, as well as being suspicious of police.

The press coverage of Alma’s death was exhaustive and never-ending it seemed. The pressure by the press and public to solve the case was mounting. The detectives slowly began to make progress.

Witnesses later came forward to police, one had said he saw a man following her, the others had stated that Tirtschke was dawdling, apprehensive and obviously afraid. At around 3pm on 30 December 1921, Alma was last seen between Bourke and Little Collins Streets, where Alfred Place runs off Little Collins Street (next to present day 120 Collins St). The Australian Wine Saloon in the Eastern Arcade was only a few meters away. It was established that while the journey should have taken Alma around 2 hours, at around 2pm she was seen turning from Little Collins Street onto Russell Street, then Bourke Street and entering the arcade again.

The police went and spoke to the owner of the Australian Wine Saloon, a man by the name of Colin Campbell Ross. He had told police that he had seen Alma pass his establishment shortly before 3pm, and then exit the arcade. She was now back on Little Collins Street a few hundred metres from where she started, having spent 90 minutes walking in a circle.

Some people would later speculate that Alma was being followed, or that something may have happened that disrupted her original plans. As the detectives were weighing up the eye-witnesses they realised that Colin was a man with a criminal record, and known for having a temper. This made him a prime suspect.

The Suspect

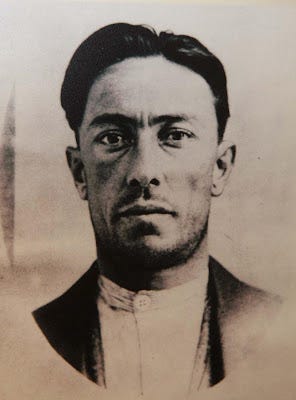

Colin Campbell Ross was a burly, strongly built man of 29 who was something of a jack of all trades. He left school at 11 and worked in laboring jobs until appendicitis left him weakened and unable to preform manual labor in his teens. He drifted between Melbourne and Sydney doing unskilled work, during the war he worked as a hospital wards man.

In April of 1921 he went into a business partnership with his mother and brother. Together they opened the Australian Wine Saloon and it quickly developed a reputation. However, due to the area of the saloon, a reputation of a different kind soon developed. It was known as a place where anyone would be served, regardless of how intoxicated they already were, or their age. The brothers were known for emptying their patrons wallets, and then turning them out, if they became rowdy.

Their activities were made known to police due to the number of complaints that followed. There were reports of drunks being passed out in the arcade as well as rowdy, late night behavior. Because of this the complaints the police started to keep an eye on the saloon. After a few months his license was revoked and the scheduled shut down was for the close of business on New Years Eve, 1921.

The year prior Colin had made himself known to the police. In May 1920 he had been arrested after he had pulled a revolver on his girlfriend, this was after she refused his proposal of marriage. Explained away as a rash act of heartbreak, Colin was only given a small fine, a suspended sentence and a good behavior bond.

Ross was interviewed by police on January 5 and 6, but the questions were of a routine nature. A week later, with public opinion inflamed and the investigation stymied, Ross was elevated to chief suspect.

He was arrested at his family home in Footscray, on January 12, 1922.

Through further investigations and searches done of Colin’s place, two blankets were found. Upon these blankets were several strands of long, brightly coloured hair. As Alma Tirtschke had striking red hair, Piggott thought he had found his smoking gun.

The hairs were sent to the Government laboratory were the Chief Government Scientist, Charles Price, conducted his tests. It should be noted that the hairs found on Alma’s body was given to Charles as well for comparison.

In the court he would testify:

'I am of the opinion that although there are slight variations in colour, length and diameter with the hair removed from the head of the deceased, the two specimens of hair were derived from the scalp of the same person.'

- Charles Price, Chief Government Scientist

Forensic science was a new concept in 1922, and viewed as something of a novelty. This would be the first time that scientific evidence involving hair samples had been used as part of a murder trial.

After securing prosecution witnesses, damaging evidence was found. One of them was a woman by the name of Ivy Matthews was a barmaid at the Australian Wine Saloon. In her original statement taken 5 January, she had said that she didn’t see Alma, nor knew nothing about what had happened. Upon her second statement she came back with a different story.

Now she claimed that Alma had been in the saloon itself on 30 December. This would place her completely in a different place to her last sightings. It would also make Matthews one of the last people to see her alive. This is because Ivy told the police that she saw Alma sitting in a private room off to one side of the bar, furthermore she claimed that Colin had given her an alcoholic drink. Ivy went one step further saying that Colin’s had confessed to the murder afterwards.

'He said that the child had been tampered with by men before. He said that he ravaged her, but did not intend to kill her.'

- From Ivy Matthews' testimony

Also a young woman named Olive May Maddox told police that she had also seen a young girl in the private room next to the bar, when she stopped for a drink on December 30.

Though it would detectives had the case wrapped up - not all was well. Just like today, the press settled on the fact that Colin was guilty even before a trial had begun. Also, Colin’s lawyers, George Maxwell and Thomas Brennan began to raise some doubts.

The forensic evidence came under scrutiny for many reasons. The hairs that Charles had said where identical were in fact not. A naked-eye examination could see that apart from being different lengths, thickness and colour; it was also discovered that Charlies Price had never examined hair samples before.

Inconsistencies in testimonies - including Ivy Matthews (which had changed several times), who gave information to the police only after it had been reported.

Matthews and Olive Maddox also admitted that they were friends and that they had met and discussed the case a number of times, both before and after Ross' arrest. This gave them time to corroborate their statements to align.

Finally, Matthews had a long-standing issue with the Ross family. She claimed that she was owed money from the saloon, and had been demanding payment.

The Trial

The trial began on 7 February 1922.

Hugh Macindoe lead the prosecution. He laid out the Crown’s evidence. This included; the accused’s past, the location of his workplace to the location of the body, the forensic evidence and the testimony of witnesses.

Ross’ lawyers pointed out the flaws and inconsistencies with every piece of evidence. Unfortunately Colin taking the stand in his defense may have sealed his fate. He spoke in a gruff, coarse manner and his appearance did not help either.

The trial lasted five days, and the jury only took one day to find Colin Campbell Ross guilty. He was sentenced to death, then still a legal punishment in Victoria. Ross was taken away in shock, while his lawyers turned their attention to an appeal.

Though the re-evaluation of evidence that was already presented could not be the basis, Colin’s lawyers found another way. They found witnesses who could back up Colin’s movements. Also this testimony debunked crucial evidence that was provided by Ivy and Olive. Witnesses, who had been in the saloon the entire night claimed that no girl was seen in the saloon.

The most stunning new evidence was the statement given by Joseph Graham, a middle-aged taxi driver. On the night of 30 December he had been walking up Little Collins Street between 3:15 and 3:30pm. As he walked past the Adam and Eve Hotel, Graham said he heard several high-pitched screams, like those of a young girl, which were quickly muffled. The alley that ran alongside the hotel was lined with cheap rooms. A lot of them were vacant and could have been the perfect place to murder Alma. Furthermore at the same time Colin was seen serving drinks to patrons at the time of the screams. Joseph explained that he had headed to the police on 9 January, intending to tell them what had happened, but without explanation he had been dismissed.

Despite this, the verdict of the first trial was upheld by the Victorian High Court. Not settling, Colin’s lawyers took the case to Sydney where on 29 - 30 March 1922 it was heard at the High Court of Australia. Once more the appeal was not successful. After this Thomas Brennan continued to lobby for a retrial; a petition was circulated that had several thousand signatures and a appeal by Colin’s mother directly to the Premier of Victoria were both to no avail.

Colin Ross was executed on April 24, 1922. His last words were, 'I am an innocent man.'

After the execution though doubts remained, it was largely forgotten. Thomas Brennan wrote a book about the trial called The Gun Alley Tragedy, in which he used to reiterate his objections to the case.

Re-examination

In the 1990’s the Ross family wanted the case re-examined.

Luckily, all the evidence from 1922 had been retained. With the advances of DNA analysis a more thorough examination could be done. The hairs on the blanket, and from Alma were actually from different people.

Along with this new evidence, legal experts looked at the trial transcripts and concluded that Colin did not have a fair trial. This included that the evidence collected was insubstantial and the witnesses’ testimonies were contradictory.

In light of the new information the Attorney General of Victoria gave Colin Ross a posthumous pardon in 2008

The murder of Alma Tirtschke remains unsolved.